One decision

Posted on by Angelo Stavrow

As I write this, I’m sitting at a Starbucks in a mall, two days before Christmas. I’m sipping a large black coffee distractedly, watching folks noodle on by, caught up in whatever last few errands they may need to run before hosting or visiting friends and family for the holidays.

The mall’s background music is calm, barely-audible, and shoppers don’t seem particularly stressed out, or rushed, or frustrated.

It’s possible that I’m projecting my mood on this scene, too. I don’t know.

This has been, for me, one of the least-stressful run-ups to the holidays ever. Part of that comes from the fact that our trips to see family are nicely spaced out this year, and part of it comes from the fact that I’ve been preparing for this since Christmas of last year.

Our flat has been perfumed with the scent of Fraser fir for weeks.

I’ve purchased all of my gifts, which I’ll be wrapping this evening.

My Christmas budget still has plenty of padding for any unexpected, last-minute purchases.

Nice.

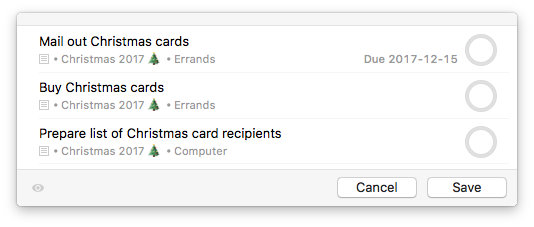

Knowing all your affairs are in order casts a lovely, warm glow on what can otherwise become a very hectic and chaotic time of year. Yeah, we missed the deadline for sending out Christmas cards—something we keep saying we want to do, but aren’t great about getting done—but otherwise, everything’s done.

Everything’s done because I made one decision during the holidays last year: make Christmas this year better.

Wishful thinking considered harmful

I used to feel that, hey, whatever, the Universe no doubt unfolds as it’s supposed to, and hopefully that means tomorrow will work out better than today did. I mean, I understood that my actions played some role in how that would play out, but, that said, there was always this feeling that things would work themselves out, because, well, they’d always somehow worked themselves out.

That is, until they didn’t.

Wishful thinking isn’t just optimism. It’s closing your eyes and hoping something works when you have no reasonable basis for thinking it will. Wishful thinking at the beginning of a project leads to big blowups at the end of a project. It undermines meaningful planning and may be at the root of more software problems than all other causes combined.

— Steve McConnell, “Classic Mistakes Enumerated”

Mr McConnell wrote this with software development projects in mind, but it’s pretty broadly applicable to almost anything. Like post-secondary education. I did extremely well with little effort in high school, so I just expected that to continue through college.

That didn’t happen.

Instead, I got pretty well acquainted with a concept called “Academic Probation”, a set of policies and procedures designed around the concept of Getting Your Shit Together.

Instead of actually recognizing that each week was going worse than the last, and taking some kind of corrective action, I kept shrugging it off and convincing myself that it’d all work out. I figured I’d ace the final, or do great on the term project, or whatever. Procrastination, anxiety, burnout, whatever the reason, I didn’t do anything to stop the downward spiral—I just fantasized about having degrees conferred and being offered great jobs.

I think life-improvement gurus call this technique “goal visualization”, but it turns out that it’s not super effective without effort.

Judge, jury, and executor

Making a decision means consciously choosing what takes priority in your life, and this also means choosing what doesn’t take priority in your life. This has, historically, been the hard part for me; your time-management system can’t manage to tack an extra couple of hours onto your day, so if you decide that project A lives, then you’re by necessity deciding that projects B, C, and maybe even D must die. If you decide that you need to buy a new car, you’re by necessity deciding that you don’t get to retire for at least another year or two.

It’s only when I realized this that I started becoming the (relatively-more-) effective and productive person I am today.

Much like the KonMari method of tidying, you need a very specific mindset when you’re going through your tasks, or your budget, or your goals, or whatever. Except the decision to keep or drop a thing isn’t going to be based on whether it brings you joy; it’s going to be based on the fact that it requires sacrificing something. Something that you once sacrificed another thing for.

Which, in turn, you sacrificed something else for.

And so on.

Looking out the top of the windshield

Generally, as people, we’re not particularly good at forethought. Mired in the day-to-day, we neglect the future until it becomes a mistake-ridden past.

Luckily, fixing this isn’t especially hard—it just takes a certain amount of mindfulness.

When I was learning how to drive, one of the best pieces of advice that I got was to pick a point about three-quarters up the windshield in front of me, and try to look above that point at least as often as I look below it. The point of this exercise was to train yourself to look as far down the road as possible, as often as possible, without ignoring what’s going on right in front of you. In doing so, you see hazards and congestions and what-have-you long before they became an unavoidable problem. You can then make small, gentle course corrections right away, smoothly merging into another lane to avoid a pothole two blocks away.

Man, I wish I’d been able to grok the life lesson in that right away.

Long-term goals influence short-term goals. The farther out you plan, the easier it is to make decisions in the near-term about what gets to stay in your life, and what has to go.

In the end, you’re really only answering a single question: does this make [tomorrow / next week / next month / next year] better?

All the to-do lists and GTD methodologies in the world aren’t going to help you, until you can make that one decision.

And yeah, we’ll be sending out Christmas cards next year.